g spot after hysterectomy

Sexual Function after Hysterectomy- Hormones Matter

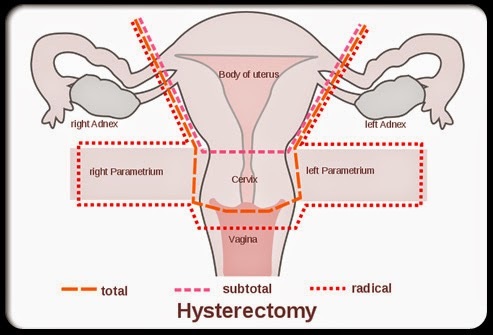

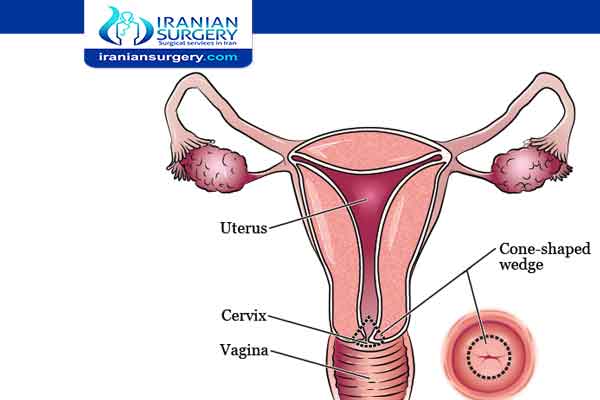

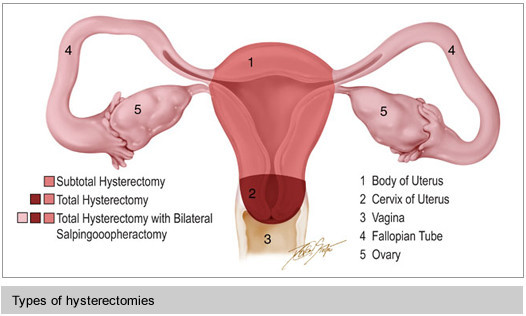

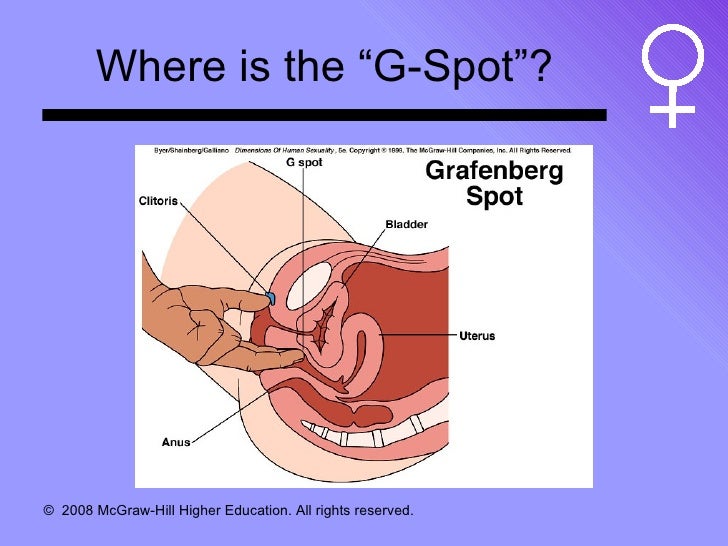

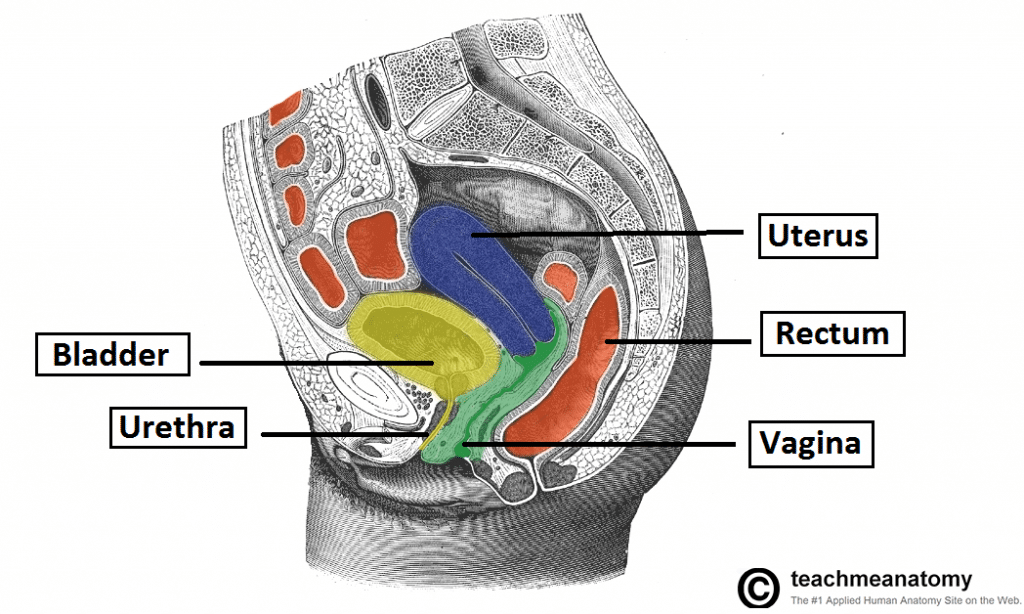

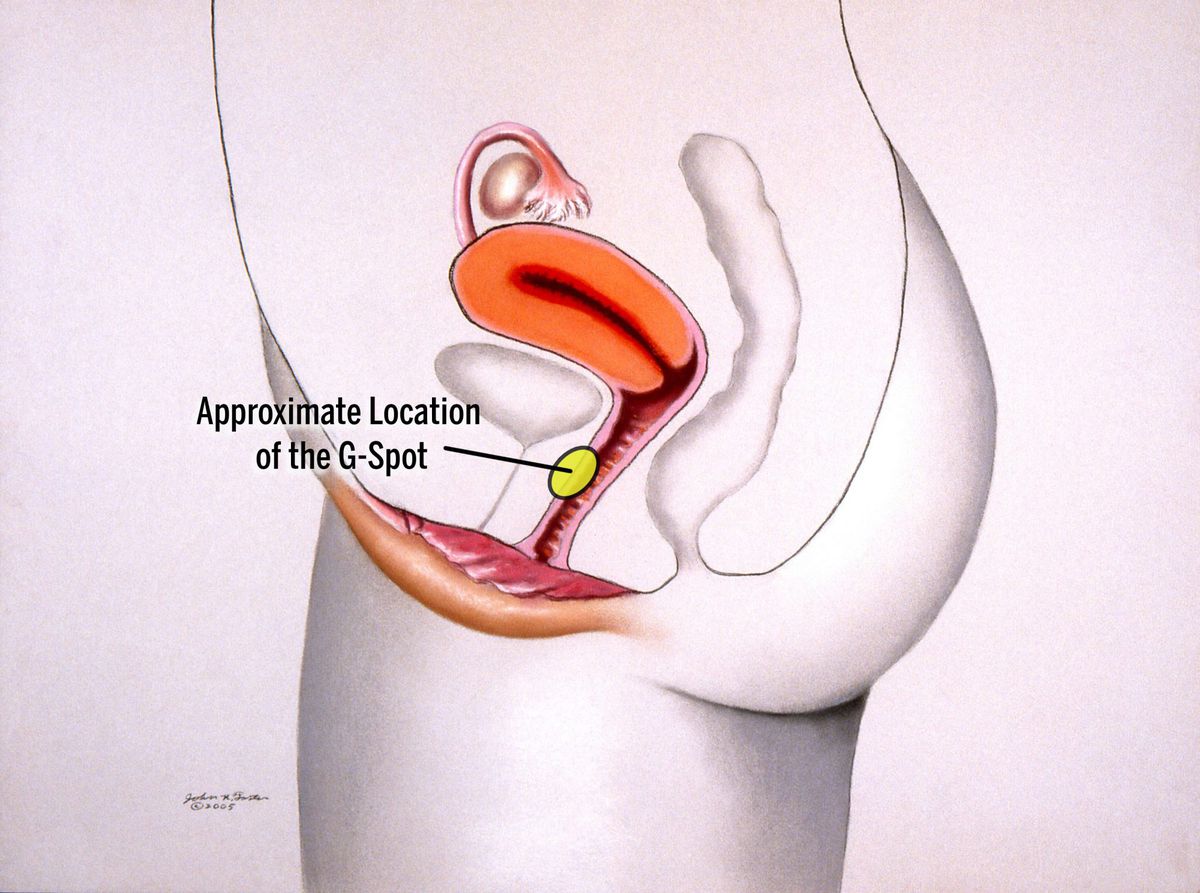

Sexual Function after Hysterectomy- Hormones MatterWarning: The NCBI website requires JavaScript to operate. Does hysterectomy improve sexual response? Addressing a crucial omission in literature Summary The predominant view in literature is that hysterectomy improves the quality of life. This is based on assertions that hysterectomy relieves pain (dispareunia and abnormal bleeding), and improves the sexual response. Since hysterectomy requires cutting the sensory nerves that supply the cervix and/or uterus, it is surprising that reports of harmful effects on sexual response are so limited. However, we note that almost all the documents we found reported that some of the women in their studies claim that hysterectomy is harmful to their sexual response. The extent to which a woman's sexual response and pleasure are likely to be affected by hysterectomy depends not only on what nerves were cut by surgery, but also on the genital regions whose stimulation women enjoy to obtain sexual response. Since the clitoral feeling (through the fetish and genitofemoral nerves) should not be affected by hysterectomy, this surgery would not diminish the sexual response in women who prefer clitoris stimulation. However, women whose preferred source of stimulation is vaginal or cervical would be more likely to experience a decrease in sensation and, consequently, the sexual response after histerectomy, because nerves that invaded those organs -- pelvics, hypogastrics and vague -- are more likely to be damaged or cut in the course of histerectomy. However, all published reports on the effects of hysterectomy on the sexual response do not specify the preferred sources of female genital stimulation. As discussed in the present review, we believe that the critical lack of information on preferred sources of female genital stimulation is key to accounting for discrepancies in literature on whether hysterectomy improves or mitigates sexual pleasure. Introduction The following quotations of women after total hysterectomy and bilateral oophoectomy are consistent with anecdotal comments to current authors by women who have suffered this surgery: Post-surgery: "...I realize a clear LACK of vaginal sensations with coitus and no longer experiences intense vaginal orgasms as I had when my cervix was intact." Post-surgery: "...I realize a clear LACK of vaginal sensations with coitus and no longer experiences intense vaginal orgasms as I had when my cervix was intact." Pre-surgery: "He (the surgeon) said, the cervix has very few nerves and is not of any sexual benefit." Post-surgery: "Now my vagina feels strange... I have no libido, and there's no feeling in my nipples. The penetration is uncomfortable, and my orgasms are weaker...." Pre-surgery: "He (the surgeon) said, the cervix has very few nervous endings and is not of any sexual benefit." Post-surgery: "Now my vagina feels strange... I have no libido, and there's no feeling in my nipples. The penetration is uncomfortable, and my orgasms are weaker...." .Post-surgery: "I will never again enjoy the intense internal orgasms I experienced when my uterus and the cervix were intact." Post-surgery: "I will never again enjoy the intense internal orgasms I experienced when my uterus and cervix were intact." Post-surgery: "Sex ... would have been great if you could still experience uterine contractions and cervical pressure..." .Post-surgery: "Sex... would have been great if you could still experience uterine contractions and cervical pressure..." It is currently estimated that more than 600,000 hysterectomies are performed in the United States per year (an average of more than one minute per minute). These are made for real and possible malignancies and benign conditions, which include pelvic pain, disparaunia, uterine fibroids (leiomyomata), adenomyosis, endometriosis and menometrorriagia. The types of histerectomy include the total (i.e., the removal of the uterus and the cervix) and subtotal ("sustitutive" or "subtravaginal", i.e. the removal of the uterus), with or without unilateral or bilateral opontomy. Surgical routes include abdominal, vaginal, and laparoscopic. Physical factors, rather than psychological, that influence these options have recently been revised by Sutton. Effects of hysterectomy on sexual response A common concern among women suffering from hysterectomy is the possible side effect of surgery on their sexual response. In this document we review the literature on the effects of histerectomy on sexual response since the review by Zussman et al in 1981. These authors took an extreme position regarding a predominant role of physiological factors rather than psychological in the sexual response after histerectomy. In their 1981 review paper, they noted that " Recent studies in the United Kingdom showed that 33% to 46% of women report a decrease in sexual response after hysterectomy-oophorectomy. The prevailing theory in the United States for more than 30 years in women's counseling is that such decreases are rare and, if they occur, psychogenic. The postulates of psychogenesis theory were examined and found no longer uneasy in the light of physiological knowledge of female sexuality, suggesting that when the sexual response is decreased after surgery, hormonal changes (including ovarian androgen) and anatomical changes (removalation of the cervix as trigger for orgasm in some women) may be etiological factors." However, subsequent studies reported that psychological factors also play an important role. For example, depression was reported to have a harmful effect not only on postoperative symptoms but also on various aspects of sexual functioning. In this review, we do not consider reports based on histerectomy made for malignancy. The following is a brief summary of the reports in which the predominant effects of hysterectomy are a decrease in disparaunia and no changes in sexual activity (frequency of sexual relations and orgasms) or libido (sexual desire). One study reported that subtotal hysterectomy ("supravaginal" or "supracervical") is more likely to preserve the orgasmic response than total hysterectomy. While the reported significant effects are summarized, it should be noted that at least some harmful effects of hysterectomy were reported in almost all documents and therefore should not be ignored. Table0 Abbreviations: + = et al; A = Abdominal; Bi/UniL= Bi/Unilateral; HRT = Hormonal Replacement Therapy; L = Laparoscopic; NC = No Change; SC = Supracervical; SCH = Supracervical Histerectomy; SF = Exual Function; T = Total; TAH = Abdominal Total•••0••0• In an extensive review of literature, Maas et al concluded that "the research on the effect of hysterectomy that has been carried out to date is not conclusive." These authors note that while most women report an improvement in sexual functioning after hysterectomy, this may be the result of the relief of symptoms (such as vaginal bleeding and disparaunia) of the sick uterus. They also conclude that a minority of women develops sexual dysfunction as a result of hysterectomy, and that more research is needed to clarify the issue of the effect of hysterectomy on sexual response. summarizes the literature on histerectomy made for benign conditions, which includes 20 articles published since 1977 that specifically tested the effects of histerectomy on sexual response, for example, reporting the effects of histerectomy on orgasm (frequency and intensity), sexual activity, libido (sexual desire), vaginal lubrication and/or "sexual function", which some papers use as a general descriptor without definition. Table 1Summary of the findings reported in the papers on the variablely reported results of hysterectomy including: effects on disparaunia, libido, sexual activity, vaginal lubrication, frequency of orgasm, intensity of orgasm and "sexual function. "*Note that in the last column – "Undesirable Effects on:" – In this category was included any individual study to report on at least some women who experienced harmful effects after hysterectomy, whether statistically significant. We believe it is important to identify and report on the incidence of harmful effects of hysterectomy on any individual. Since very few documents produced on these harmful effects, we cannot distinguish whether women who, for example, experienced disparaunia after hysterectomy developed this condition after surgery or if the condition was present preoperatively but did not merge with surgery. Summary of 20 documents (1977-2007) EffectIncreaseIncreaseNo changeVariableUndesirable Effect on:Dyspareunia082012 Sexual activity211017 Frequency of orgasm12507 Intensity of orgasm10313 Vaginal lubrication10406Libido3110013 Sexual function21202 summarizes, in greater detail, the findings in these documents. It is difficult to discern a consistent pattern between these reports, perhaps due to factors that include: the complexity of the inervation of the sexual system, the various types and the surgical routes of histerectomy, the various sources of sexual stimulation, the symptoms of presentation (e.g. pain and/or bleeding), the surgical methodology - the path of access (vaginal, abdominal, laparoscopic), the degree of surgery. In addition to alleviating the discomfort of pain and bleeding from hysterectomy, positive psychological factors such as the elimination of cancer risk anxiety and unwanted pregnancy can overcome negative factors, especially the possible loss of genital sensitivity. Rhodes, et al. stated, "This relief of symptoms may have led to greater sexual enjoyment and increased frequency of orgasm. In addition, in terms of sexual functioning, improvements due to symptom relief may have exceeded any lost feeling due to the removal of the cervix. "The mule factors have been proposed as a basis for harmful effects of hysterectomy in the sexual response. These include: (a) the uterus negatively affects some women for whom uterine contractions were an important aspect of orgasm, (b) scarring tissue that prevents a full balloon from the vagina, which can make it difficult to coiture because the vagina is less expansive, and (c) internal healing or nervous damage causing pain or interfering with feeling of sexual pleasure. In addition, after a hysterectomy, d) the reduced amount of tissue resulting in reduced vasocongestion can reduce sexual excitation as well as the probability of multiple orgasms, and hysterectomy may affect sexual function by e) disrupt local nervous supply, vaginal blood flow and anatomical relationships, which could have a negative effect on the overall pelvic function. In addition to these factors, the pathology of histerectomy can differentially affect the sexual response. Thus, in his recent study, Peterson, et al. "Women who had hysterectomy due to endometriosis reported more difficulty and less satisfaction with orgasm than women who had hysterectomy for other reasons." In addition, "...there was no significant difference in women's perception of their pre- and post-hysterectomy sexual functioning based on whether women did not receive OST (bilateral salpingo-oophoretomy), a OST with HRT (hormone replacement therapy), or a OST without HRT" Based on the other papers we review, it is not possible to draw a conclusion on the hormone of sexual effectiveness. Nearly half of the documents do not specify whether HRT was administered, other documents report that some of the women in their study received oophorectomy, and some received HRT, but the contingent relationships are not specified between these procedures and any of the sexuality measures. If we consider only the subgroup of papers in which the hysterectomy was performed for the myoma or endometriosis, or any non-evil condition for which the hysterectomy was performed, the lack of reported contingencies between these variables further weakens our ability to relate any of these procedures to their effects on reported types of sexual responses. Research on Genital Sensitivity After the previous consequences of hysterectomy are considered, the specific issue of genital sensibility after hysterectomy continues to exist, for which there is a shortage of experimental tests. To address this problem, consider first the evidence of clitoris, vaginal and, cervical inervation and sensibility in women where these aferent pathways are intact. The obvious questions are: (a) What is the evidence of the inervation of the genital organs, (b) are the sensate genital organs, (c) histerectomy affects the sensitivity of the genital organs, and (d) make changes induced by histerectomy in the genital sensitivity explain the effects of surgery on sexual responses? We refer to these questions in sequence, as follows:a) Evidence of the inervation of the genital organsZussman et al were of the opinion that the vagina has no nerve endings. They agreed with Clark and Singer's and Singer's opinion that the internal genital sensitivity was due to the stimulation of the vagina and the cervix per se, but rather to the pleasurable sensation resulting from the penile-induced movement of the peritoneal membranes surrounding the uterus and its supporting ligaments. On the contrary, Dimond and Montagna declared, "Despite previous reports on the contrary, the human vagina and the cervix are profusely invaded." Krantz had described an unusual wavy pattern of nerve fibers in vaginal adventia (i.e., the connective tissue covering the vagina in the abdominal cavity) and the vaginal musculature, and suggested that the wavy pattern could provide a means by which the nerve ends could adapt to extreme distortion resulting from childbirth and childbirth. Blank et al later reported that the vagina and cervix contain high concentrations of NPY and VIP immunoreactive nerves, located around the vascular and non-vascular smooth muscle. Most recently Pauls et al described vaginal nerves regularly located along the anterior and posterior vagina, proximal and distally, including apex and cervix. They did not find vaginal location with increased nerve density. A type of final nerve (third "Merkel Receiver") that specializes to respond to constant pressure was found in the region introitus vaginal but not elsewhere. In that region a clear difference was reported in the inervation of the deep (submucosal) layer of vagina tissue. The connective tissue of the previous wall was found to be richly inervaded, by contrast to the posterior wall, which was more spariously inervated. The division of labour between genital sensory nerves is basically the following. In women, the hypogastric nerves transmit aferent activity of the uterus and the cervix, the pelvic nerves transmit aferent activity of the vagina, and the nerves canndal convey clitoral activity, , , , . More specifically, DeLancey affirms that "the blocked of the lip canndal abolishes the sensation of pain, , . Mons pubis, labia and vulvar skin receive afferents through the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves, which enter the spinal cord in L 1 and L1-2, respectively. Potential and pelvic nerves enter the spinal cord at the Sacral 2-4 levels and the hypogastric nerves travel in the sympathetic chain and enter the spinal cord at the Thoracic 10-12 levels. Recently there has been evidence that a fourth pair of nerves – the Vagus – transmit the afferent activity of the cervix and the vagina.b Evidence that the vagina, cervix and clitoris are sensateKinsey et declaring a conclusion on the ability of women to perceive vaginal and cervical stimulation which, notably and surprisingly, diametrically contradicted their own data. As for vaginal sensitivity, they said, "In view of the evidence that the walls of the vagina are generally insensitive, it is obvious that the satisfaction obtained from vaginal penetration should depend on some mechanism that is outside the vaginal walls themselves." Then, in terms of cervical sensitivity, they said, "All clinical and experimental data show that the surface of the cervix is the most insensitive part of female genital anatomy. About 95% of the 879 women tested by gynecologists for this study did not fully know that they had been touched when the cervix was shed or even slightly pressed [their Table 174]. Less than 5 per cent were more or less aware of such stimulation, and only 2 per cent of the group showed more than local and vague responses (p. 584). Contrary to its own claim, the examination of its Table 174 shows a marked difference in the response to the pressure... tested by exerting a different pressure on the points indicated with a larger object than a probe, compared to the "tactil" stimulation, which was "made with a glass, metal or cotton probe with which the areas indicated were gently stroked". In response to this pressure stimulation, 89 percent of the 879 women in their study responded to the stimulation of the previous vaginal wall, 93 percent of women responded to the stimulation of the posterior vaginal wall, and 84 percent of women responded to the stimulation of the cervix! Upon reaching its conclusion, the authors focused on the soft touch stimulation of the vagina and the cervix, while ignoring the effect of pressure stimulation that is obviously a much more relevant stimulus during the penis-vaginal intercourse. Despite clear evidence of vaginal and cervical sensitivity to adequate physical stimulation, it seems to be a fairly widely held belief that the vagina and the cervix are foolish. There is another evidence of functional sensory activity of the cervix. In one study, 77 percent of 137 women showed reflexive contraction of the bulbocavernous muscle, which produced clitoral motion or contraction of the muscle of the thigh in response to touching the cervix during the eyelid procedure. In another study, electrical stimulation through electrodes in the cervical canal produced the disincronization of the cortical alpha rhythm during which women reported that they perceived stimulation. With repeated tests that systematically decreased the intensity of stimulation, women realized cervical stimulation in intensity that were previously underestimated for their perception. Perry and Whipple found that the anterior wall of the vagina, that is, the region near the "12" (with the woman who lies supine), was more sensitive to physical stimulation, and stimulation through that region (called the "Grafenberg Point" or "G Point") was more likely to produce orgasm than stimulation from other regions of the vagina. The back wall, about 6 o'clock, was less likely to cause orgasm. In a separate set of experiments, we find that in the case of another type of response to vaginal stimulation (auto-) in women, that is, the suppression of pain, the mechanical stimulation of the anterior wall of the vagina was more effective in the suppression of the pain caused experimentally (measured by the application of the calibrated force, gradually increasing, compressive to the fingers) than the stimulation of the posterior wall of the vagina. Alzate and Londono described the procedures they used to conduct a sensibility study of the vaginal regions in women. Between 48 women, 94 percent reported vaginal erotic sensitivity. Between 30 proven women who experienced orgasm or approached orgasm, 73 percent showed a maximum response to the stimulation of the upper half of the previous vaginal wall, and 27 percent had a maximum response to the stimulation of the lower half of the previous vaginal wall. In 30 percent another area, whose stimulation could cause an orgasmic response, was in the lower half of the posterior vaginal wall (some subjects showed more than one maximum response zone). The authors claimed that very few reported a pleasant sensation in the cervical or posterior vaginal fornix. However, in our lab, in a study where more than 20 women applied mechanical pressure directly to the cervix using a stimulator designed as it adhered to a diaphragm installed on the cervix, most women reported feeling the stimulus, and we were able to measure their pressure sensitivity threshold. Some of the women who had suffered a "complete" spinal cord injury at the chest or higher levels than the cervix could feel the stimulation of the cervix, although they were less sensitive to stimulation than uninjured women. Two of the women stated that when they pulled the stimulator out, far from the cervix, the suction generated by the diaphragm against the cervix felt unusual and pleasant. When we record brain activity using the FMRI, in response to cervical self-stimulation in these women, we find the activation of the region of the nucleus of the lone tract, to which the Vagus nerve project, in the oblongata medulla of the brain trunk. In women with body, we are finding that cervical self-stimulation activates the genital sensory cortex (specifically, the paracentral lobe; ).Localization of the cortical sensory response to the self-stimulation of the cervix. The arrow points to the answer in the paracentral lobe, adjacent to the post-central turn. Another activity is related to the hand movement used to apply stimulation. Coronal view; group data, N=11. Consequent to this description of the pleasurable response to cervical stimulation, Cutler et al reported that 35 percent of 128 healthy women declared that they experience orgasm due to the stimulation of the cervix neck during sexual intercourse. In the same study, 63 percent of women reported experiencing vaginal stimulation orgasm and 94 percent reported experiencing clitoral stimulation orgasm. The authors did not report the proportions and varieties of specific combinations of individuals between these sources of stimulation. Using a different method to measure sensitivity – soft electrical stimulation to different intensities – Weijmar Schultz et as tested the sensitivity of different regions of the vagina. They were called the most anterior region of the vagina (i.e., the region closest to the clitoris) "12 by point" and the region closest to the year "6 by point". They found that the region of 12 o'clock in the vagina was more sensitive. All internal vaginal areas around the clock were less sensitive than clitoris. The clitoris had a slightly greater sensitivity than the lower lips. The older lips were slightly more sensitive than the clitoris and minor labia. The abdominal skin and the back of the hand were more sensitive than all previous genital regions. A particular type of sensory receptors -- Pacinian corpuscles -- which are specialized in responding to pressure and vibration, found themselves present in greater numbers in the clitoris and the foreskin than on the lower lips. The clitoris has been characterized as the "most densely inervated part of the human body." (c) Evidence that histerectomy affects genital sensibility Based on the above-mentioned evidence of clitoral inervation, vagina and cervix, it would not be surprising if the responses to genital stimulation are numbed by histerectomy. Several studies have reported on these effects. Thus, Hasson said, "The cervix is not a useless organ and should not be eliminated during hissterectomy without proper indication.... The loss of an important part of the uterovaginal plexus (Frankenhauser) through the excision of the cervix is obliged to have an adverse effect on sexual excitement and orgasm in women who previously experienced internal orgasm." This effect had been stated earlier, i.e., "In 1973, in a personal communication, the Masters noted: "Many women certainly describe cervical pressure as a mechanism for activating coital responsibility. Such women can be and occasionally are sexually disabled when this trigger mechanism is surgically eliminated'" . The same authors also stated: "For some women, the quality of orgasm is related to the movement of the cervix and neck of the uterus, and for these women the intensity of orgasm is diminished when these structures are eliminated. For other women, orgasm is achieved mainly by clitoral stimulation so that the loss of internal structures does not have a comparable effect. Consistent with this assertion, the measurement of vaginal sensitivity and clitoris 3 months after histerectomy, compared to immediately before surgery, showed that there was a small but significant reduction in the sensitivity to cold and warm stimuli in the anterior and subsequent vaginal wall, while clitoris sensitivity was not affected. The effect of cervical excision in the sexual response was shown by Kilkku et al, who reported in a study of 212 women that the removal of the cervix in total hysterectomy was associated with a lower incidence of orgasms than subtotal hysterectomy, in which the cervix is saved. Thus, the percentage of women who experience less than 1 orgasm for 4 coital events increased significantly after total hysterectomy of 29.7 pre-surgery at 46.7 to 12 months after surgery, while at the same interval after subtotal hysterectomy, there was a non-significant change of 28.6 to 32.0, respectively. A recent study in the United Kingdom based on a 5-year questionnaire after surgery sent to women who had been surgically treated by "disfunctional uterine bleeding" supported this difference in the effects of total and subtotal hysterectomy. Of the more than 8900 women who responded to questions related to their psychosexual function, ...more women reported having an an annoying psychosexual function [i.e., "loss of interest in sex, difficulty getting sexually excited, and vaginal dryness"] than women who had a less invasive operation [i.e., transcervical endometrial resection/abllation, or subtotal hypohortomy] Hormonal therapy, although related to the surgical method, did not reduce this long-term harmful effect. The odds were particularly high among women with simultaneous bilateral oophorectomy." On the contrary, Roussis et al in a questionnaire study of 400 women within 3 years of hysterectomy of various types, including total and supracervical abdominal, concluded that the responses that referred to libido, sexual activity or femininity feelings did not reveal significant changes in prehysterectomy levels. Farrell and Kieser came to a similar conclusion, which examined 18 reports in the literature. They concluded that while "external measures were generally not validated and most studies did not consider important factors of confusion.... Most of the studies in this review showed neither a change nor an improvement in sexuality in women who had a hysterectomy." In a meta-analysis entitled, "Role of the cervix in sexual response: evidence for and against", Grimes in 1999 highlighted methodological deficiencies of all relevant studies, concluding "The evidence both for and against a role for the cervix is weak," and that "if the subject is truly important for more than half a million American women who have a hysterectomy every year, then gynecologists have an ethical obligation to control." Therefore, there is no clear evidence that the cervix does not play any role in the sexual response. Few studies examine or ask women about the role of the cervix in their sexual response. In the case of subtotal hysterectomy, cervical sensitivity is likely to be compromised by damage to its three different pairs of sensory nerves, and, of course, abolished by total hysterectomy. Thus, the absence of evidence of a sensory role for the cervix in the sexual response should not be interpreted as evidence of its absence.d) Does the changes induced by histerectomy in genital sensitivity explain the effects of surgery on the sexual response? We propose the following hypothesis to reconcile the discrepant assertions of the effects of hysterectomy: There is a brilliant omission in all literature that we have reviewed on the effects of hysterectomy on the sexual response – is the report of women from their preferred source of genital stimulation. The importance of this factor has been pointed out by Goetsch: "The locus of orgasm can affect the impact of hysterectomy.... The most common sites were clitoris (for 30% of respondents), vagina (11%), and uterus and vagina (8%). (These percentages do not add up to 100% because the question was made evidently about the orgasm locus for each of these sites individually). While this refers to the site of the body in which orgasm is perceived, it does not address the crucial question of the site of the body from which orgasm occurs, that is, the specification of the preferred source of stimulation of an individual woman. Therefore, if a woman prefers clitoris stimulation, we would not expect any blurry effect of hysterectomy in the sexual response. However, if you prefer vaginal and/or cervical stimulation, the sensitivity of these organs may be compromised by surgery. After taking into account the effects of hysterectomy in reducing pain and bleeding, we believe that the effects of histerectomy in the sexual response will be related to the remaining sensitivity of the cervix, vagina and clitoris. The insufficiency of data on genital sensitivity in relation to the sexual response has been pointed out by Mokate, et al: "The evidence lacks sexual dysfunction caused by the disturbance of the local nerve...supply". Taking into account the dual factors of genital sensitivity and the preferred source of stimulation would play an important role in accounting for discreet reports on the effects of hysterectomy on sexual response. Conclusion We conclude that the variability of the reported effects of hysterectomy in the sexual response may depend on whether surgery desensitizes the preferred genital site of the female stimulation. The studies discussed in this document almost universally do not address this contingency. Other research that takes these factors into account together can help reconcile the reported variability of the effects of histerectomy on sexual response. Acknowledgements Financial support: NIH subvention 2R25GM060826-09 Footnotes None of the authors have financial interest in this workDelections of Editor: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will be submitted to copy, composition and revision of the resulting test before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process you can discover errors that could affect the content, and all legal claims that apply to the journal. ReferencesFormats: Share , 8600 Rockville Pike, Bethesda MD, 20894 USA

G‐Spot Anatomy and its Clinical Significance: A Systematic Review - Ostrzenski - 2019 - Clinical Anatomy - Wiley Online Library

Is It Possible to Have an Orgasm after a Hysterectomy?

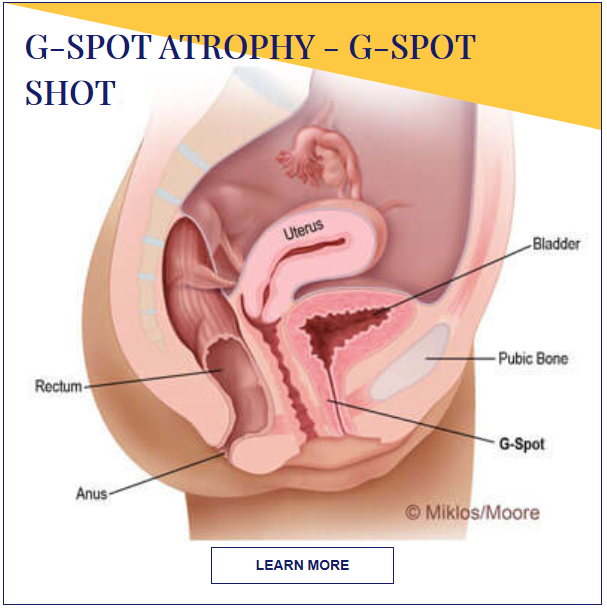

G-Spot / O Shot - Kamol Cosmetic Hospital

Amplification of the G spot | augmentation of G spot | Dr N Layyous

Amplification of the G spot | augmentation of G spot | Dr N Layyous

G-Spot Atrophy Atlanta | G-Spot Shot Beverly Hills | ThermiVa Dubai

The "G-Spot" Is Not a Structure Evident on Macroscopic Anatomic Dissection of the Vaginal Wall - The Journal of Sexual Medicine

Can't Find my "G-Spot" | Intimacy After Hysterectomy Article | HysterSisters

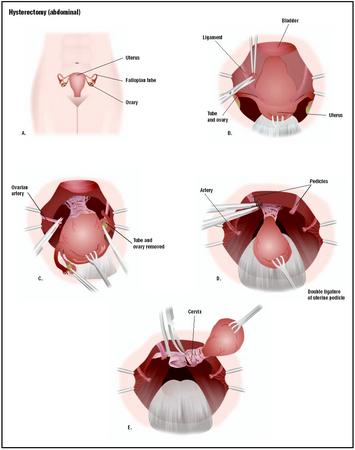

vaginal hysterectomy | Vaginal hysterectomy recovery , steps , procedure

The "G-Spot" Is Not a Structure Evident on Macroscopic Anatomic Dissection of the Vaginal Wall - The Journal of Sexual Medicine

💄👫👈Does Hysterectomy Affect the G-Spot and Other Questions About Sex Without II HEALTH TIPS 2020💄👫👈 - YouTube

Sex After a Hysterectomy: What to Expect and How to Actually Improve Your Sex Life

G-Spot / O Shot - Kamol Cosmetic Hospital

Hysterectomy Surgery | Uterus Surgery | Frisco, Dallas, Plano | TX

Q&A: Orgasm After Hysterectomy? | Christian Nymphos

G-Spot After Hysterectomy: Guide to Orgasm Post-Op

Pelvic Organ Prolapse (POP) Treatment - Visionary Centre for Women

Robotic Sacroculpopexy for Pelvic Organ Prolapse | The Urology Group of Virginia

Womens Health 8

Menstrual Cups & Prolapse - Can You Use a Menstrual Cup?

Endometrial Ablation - Hysterectomy Alternative or Trap?- Hormones Matter

Female Anatomy After Hysterectomy - Anatomy Drawing Diagram

Removal of Uterus surgery Mohali chd | Singla Mediclinic

Menstrual Cups & Prolapse - Can You Use a Menstrual Cup?

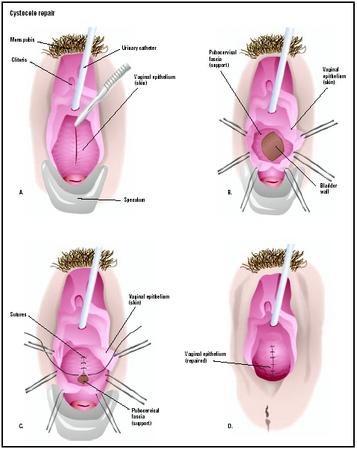

Cystocele Repair - procedure, recovery, tube, removal, pain, complications, time, infection

The A-spot is the sexual pleasure point that could unlock the best orgasms of your life

Vaginal vault - Wikipedia

The "G-Spot" Is Not a Structure Evident on Macroscopic Anatomic Dissection of the Vaginal Wall - ScienceDirect

Female Anatomy After Hysterectomy - Anatomy Drawing Diagram

How To Find Your G-Spot | Allure Medical

A Hysterectomy Should Not Stop You From Having Great Sexual Health

G-Spot After Hysterectomy: Guide to Orgasm Post-Op

Hysterectomy - procedure, recovery, blood, tube, removal, pain, complications, time

Saying Goodbye to My Uterus - Preparing for a hysterectomy can be tough. Here's one woman's letter to her ut… | Uterus, Uterine cancer quotes, Hysterectomy recovery

Sex after a hysterectomy - How long to wait after a hysterectomy to have sex again

Postpartum hemorrhage: Management approaches requiring laparotomy - UpToDate

Where Does Sperm Go After a Hysterectomy? The Facts

Postpartum hemorrhage: Management approaches requiring laparotomy - UpToDate

The G-Spot: What It Is and How to Find It | Health.com

Posting Komentar untuk "g spot after hysterectomy"