interferon long term side effects

Interferon: Long-Term Side Effects

Interferon: Long-Term Side EffectsHepatitis Research and Treatment On this pagePegilated Interferon and Ribavirin Treatment for Hepatitis C Virus InfectionReview Article ← Open AccessTatehiro Kagawa, Emmet B. Keeffe, "Long-Term Effects of Antiviral Therapy in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C", Hepatitis Research and Treatment, vol. 2010 Article ID 562578, 9 pages, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/562578Long-Term Effects of Antiviral Therapy in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis CTatehiro Kagawa1Department of Gastroenterology, School of Medicine of the University of Tokai, Shimokasuya 143, Isehara 259-1193, Japan2 Emerging data show that interferon-based therapy, in particular among those that achieve sustained virological response (SVR), is associated with the long-term persistence of SVR, the improvement of fibrosis and inflammation scores, the lower incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma and long-term life expectancy. This reduction in the rate of progression has also been shown in patients with chronic hepatitis C and cirrhosis in some but not all studies. Most of these results are reported with standard interferon therapy, and long-term results of peginterferon plus ribavirin therapy with a higher probability of SVR should have an even greater impact on the population of treated patients. The impact on slow progression is greater in patients with a SVR, less in relapses, equivocal in non-repressants. Thus, the natural history of chronic hepatitis C after the termination of antiviral therapy is favorable with the realization of a SVR, although more data is needed to determine the probable incremental impact of peginterferon more ribavirin, late long-term effects of therapy, and the benefit of treatment in patients with advanced liver fibrosis.1. IntroductionThe Hepatitis C virus (HV) is a major cause of chronic liver disease and a major public health problem, with 130 to 170 million people infected worldwide []. Chronic HV infection can lead to severe sequelae, such as final stage cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (CCA), the need for liver transplantation and premature death []. The treatment of HCV infection with interferon was first successfully used in 1986 [], and the interferon in its pegilated formulation in combination with ribavirin is the preferred therapy for the treatment of patients with acute or chronic HCV infection []. The current treatment of chronic hepatitis C is peginterferon alpha-2a or alfa-2b more ribavirin, with approximately 55% to 65% of patients of all genotypes achieving a sustained virological response (SVR) [–]. However, only 42% to 52% of patients with genotype 1 infection have a SVR after 48 weeks of combined therapy in pivotal trials [–]. SVR is traditionally defined as an undetectable HCV RNA serum 24 weeks after the discontinued therapy and is regarded as a "cure" [], although an undetectable HCV RNA 12 weeks after the termination of therapy seems to be equally relevant to the prediction of a SVR in patients treated with peginterferon more ribavirin []. The main objective of chronic hepatitis C treatment is to prevent late liver morbidity and mortality, and the measurement of SVR is the short-term substitute used to predict the long-term effectiveness of antiviral therapy. The aim of this concise document is to summarize the current knowledge of the impact of antiviral therapy on the persistence of VHR and long-term results, including the impact on liver fibrosis, the incidence of CCA and life expectancy. These data provide a justification for the early use of antiviral therapy not only to achieve a SVR but also to positively impact the long-term prognosis of chronic hepatitis C.2. Sustained Virological Response Persistants Term Length The first study shows that a sustained response to antiviral therapy was associated with long-term biochemical and virological responses, as well as histological improvement was reported by Marcellin and colleagues from France []. In this study of 80 patients who had a sustained biochemical and virological response of 6 months, the average follow-up of 4 years showed that 93% of patients had a persistently normal aminotransferase (ALT) level and 96% had an undetectable serum RNA. A comparison of liver histology before and 1-6.2 years after the termination of interferon therapy showed improvement in 94% of patients, and HCV RNA was undetectable in the liver in 1 to 5 years after treatment in the 27 patients tested. In an analysis of 4 large trials in which 395 patients were followed after achieving an alpha-2b interferon with or without ribavirin, the actuarial probability of maintaining the response after an average follow-up of 5 years was 99% 1%, with 10 patients in general (2.5%) developing HCV detectable RNA and all within 2 years of follow-up []. Therefore, this analysis of a large study database confirmed that late relapse is rare in patients who remain negative HCV RNA 24 weeks after termination of interferon therapy. Several other studies [, –], including a small study with an average follow-up of 10 years [], showed that SVR predicts a high probability of long-term SVR (Table ). One of these studies followed 344 patients for an average duration of 3.3 years (range, 0.5 to 18 years) after the termination of interferon therapy with a SVR, and showed that the serum HCV RNA remained undetectable in 1300 samples, indicating that none had a relapse with up to 18 years of follow-up []. It is unclear whether late detection of serum HCV RNA after a SVR in a small number of patients represents true relapse, especially if detection occurs only once or is intermittent and with the use of a very sensitive trial. Although additional follow-up studies can provide further clarification on this distinction, a SVR appears to be for now durable and a precise reflection of a cure. Author, year of publication (reference)Patients no. Follow-up yearsDetectable HCV RNA no. (%)Marcellin et al. []804 (mean)3 (4)Reichard et al. []265.4 (mean)2 (8)McHutchison et al. []395; 1515 (mean)10 (2.5%); 2 Veldt et al. []286Up to 4.912 (4)Formann et al. []1872.4 (median)0 (0)Desmond et al. []1472.3 (mean)1 (0.7)Lindsay et al. []3664.8 (mean)4 (1)Maylin et al. []3443.3 (mean)0 (0)George et al. []1475.4 (median)0 (0); 9 Kim et al. []73No not reported8 (11); 1 Patients in previous studies that were followed after a SVR are heterogeneous and include those with all genotypes and various treatment regimes, including interferon monotherapy, more ribavirin interferon and more ribavirin peginterferon, and several treatment durations for 24 or 48 weeks; patients were generally naive to previous therapy, but included. 395 patients with SVR and participants in 4 studies were followed, including naive and relapsed patients, and patients were treated with interferon monotherapy or more ribavirin interferon for 24 or 48 weeks; of these 395 patients, a subset of 151 patients were naive and received more ribavirin interferon for 48 weeks. No patient had detectable HCV RNA using PCR (sensitivity = 29 IU/mL); 9 patients had detected HCV RNA by AML (sensitivity = 5.3 IU/mL) in a sample (average 4 samples of the 9 patients), but all other samples of these 9 patients were negative by AML. HCV RNA was detected by qualitative RCP in 8 patients, but only one patient had persistent viremia. Author, year of publication (reference)Patients no. Follow-up yearsDetectable HCV RNA no. (%)Marcellin et al. []804 (mean)3 (4)Reichard et al. []265.4 (mean)2 (8)McHutchison et al. []395; 1515 (mean)10 (2.5%); 2 Veldt et al. []286Up to 4.912 (4)Formann et al. []1872.4 (median)0 (0)Desmond et al. []1472.3 (mean)1 (0.7)Lindsay et al. []3664.8 (mean)4 (1)Maylin et al. []3443.3 (mean)0 (0)George et al. []1475.4 (median)0 (0); 9 Kim et al. []73No not reported8 (11); 1 3. Natural History of Chronic Hepatitis CThe progression of HCV infection is relatively slow, and the risk of developing cirrhosis varies from 4% to 25% in infected people over 20 to 30 years of follow-up [, –]. The oldest age at the time of HCV infection, male gender, obesity, immunosuppression and heavy alcohol intake are associated with a faster rate of progression [–]. The annual development rate of HCC in the presence of cirrhosis ranges from 1 to 3 per cent in Western countries to 5 to 7 per cent in Japan [–]. The highest proportion of patients with HV-infected age in Japan can explain the highest incidence rate in this country, as the advanced age accelerates the development of CCA []. Hepatic decompensation of cirrhosis occurs at a rate of 3% to 4% per year [, ].4. Antiviral therapy improves hepatic fibrosis and inflammation Changes in histologic findings after an interferon therapy course have been studied extensively. Shiratori and colleagues analyzed liver biopsies of 593 patients; 487 received interferon monotherapy for no more than 6 months and 106 were not treated. Fibrosis returned to a rate of 0.28 Metavir units per year in those that achieved a SVR. A meta-analysis of data of 1,013 patients of 3 large randomized trials [–] showed that the treatment of peginterferon reduced inflammation and fibrosis in patients with or relapsed RVS, but not in non-receptors []. This improvement was more prominent with the use of peginterferon instead of interferon. A significant improvement has also been shown after the use of peginterferon and ribavirin combination therapy, with the achievement of SVR []. Even in patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis, inflammation and fibrosis were improved with interferon monotherapy, peginterferon monotherapy, or peginterferon plus ribavirin combination therapy [–]. In a dataset of 3,010 naïve patients with pre-treatment and post-treatment biopsies form 4 randomized trials of 10 different regimes using combinations of standard interferon alfa-2b, peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin, it was shown that there was an improvement of 39% to 73% in necrosis and inflammation []. In addition, all regimes significantly decreased rates of progression of fibrosis compared to rates before treatment, with the best results observed with peginterferon more ribavirin. In particular, cirrhosis was invested in 49% of patients with baseline cirrhosis. Six factors were associated with the absence of significant fibrosis after treatment: basal fibrosis stage, SVR, age 40, body mass index 27 kg/m2, reference activity no or minimal, and HCV RNA level 3.5 million copies/mL []. In contrast to the study of Cammà et al. [], the analysis of Poynard and colleagues showed a slowness of the natural progression of fibrosis in non-receptors, as well as those with a SVR and relapse []. A limitation of both studies is the relatively short time between biopsies paired, that is, before treatment and 24 weeks after the termination of therapy. In short, antiviral therapy studies with interferon monotherapy, peginterferon monotherapy or peginterferon plus ribavirin combination therapy demonstrate an improvement in inflammation and fibrosis in patients with SVR, to a lesser degree in relapse, and uncertain benefit in noresponders.5. Antiviral therapy is associated with a lower incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma The Hepatocarcinogenic Inhibition by Interferon Therapy (IHIT) Study Group in Japan has been studying the development of HCC in approximately 3,000 Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis C and has shown that interferon therapy reduces the risk of HCC in half, including up to a fifth in non-chemical or virological response.] The preventive effect of the interferon on the development of HCC was also reported by Imai et al. [], which performed a retrospective study of 419 patients who received interferon monotherapy for 6 months and compared the incidence rate of HCC with nontreated controls. Relative risk (RR) for HCC was 0.06 () in patients with SVR, and 0.51 () in relapses, and 0.95 () in non-repressors, indicating that only one SVR was associated with a reduced risk of HCC. On the other hand, another study showed that the incidence of HCC was reduced not only in patients with SVR, but also in relapses compared to non-receptors []. Compatible with the above studies, the IHIT Study Group has also shown reduced inflammation and fibrosis in patients with VR []. However, it should be noted that a reduction in the risk of HCC does not necessarily indicate the improvement of overall survival, and the interferon is less effective in patients with cirrhosis. In addition, cirrhotic patients tend to be older, and liver-related mortality can be significant and obscure any potential benefit of interferon therapy.6. Life expectancy extends with interferon-base therapy Long-term durability of a SVR, improvement of fibrosis and inflammation, and a decrease in the incidence of HCC is expected to translate into a long-term life expectancy. In fact, recent follow-up studies long enough are reporting this last final point of antiviral therapy [, –]. In a retrospective cohort study of 7 university hospitals and 1 regional central hospital in Japan, 2,889 patients with biopsies were analyzed, including 2,430 patients who received interferon and 459 nontreated patients []. Compared to the general population, overall mortality was high among patients not treated but not among patients treated. In patients treated by interferon, the risk of death associated with the liver was reduced compared to nontreated patients, while the risk of non- liver death remained unchanged. In another study of 459 patients followed by an average of 8.2 years, the multivariate regression analysis revealed that interferon treatment decreased the risk ratio for general death and liver-related death, especially in patients with SVR []. Again, the interferon showed no association with death related to the liver. Another retrospective study of cohorts of 2,954 patients, including 2,698 treated and 256 nontreated, showed similar results []. During an average follow-up of 6 years, interferon therapy improved survival in chronic hepatitis C patients that show a biochemical and virological response avoiding liver-related deaths. Finally, a prospective follow-up study of 6.8 years of 345 patients with cirrhosis, of which 271 were treated and 74 were not treated, showed that the interferon inhibited the development of HCC and also improved survival []. In contrast to previous findings, an Australian study showed that the treatment of IFN reduced liver complications, but the beneficial effect of achieving a SVR was marginal () in a multivariate analysis [].7. Impact of antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C and cirrhosisWhat about the impact of antiviral therapy on patients with chronic hepatitis C and cirrhosis? Shiratori et al. [] carried out a prospective study on 345 cirrhotic patients, of which 271 received interferon monotherapy for a median of 6.5 months, evaluating the cumulative incidence of HCC and survival in relation to 74 nontreated patients; SVR was reached in 15% of these patients. In patients who achieved a SVR, the age-adjusted risk ratio (HR) for the development of HCC and death was significantly reduced to 0.31 () and 0.05 (), respectively, while the results for those who did not reach a SVR were not significantly different from the control group. Bruno et al. [] performed a retrospective study of cohorts of 920 cirrhotic patients treated with interferon monotherapy for 1 year, which resulted in a rate of 13.5 per cent of SVR. Failure to comply with a SVR had a higher risk of complications related to the liver, HCC, and liver-related mortality. 33% of the patients achieved a SVR after the combined peginterferon therapy more ribavirin and had better results than those who did not achieve a SVR []. Multivariate analysis revealed that the inability to achieve a SVR was associated with a higher risk of liver, HCC and liver-related mortality compared to those who achieved a SVR. However, several studies have shown no beneficial effect of IFN therapy on the prognosis of cirrhotic patients [, , ]. A lower rate of SVR (4%–9%) or a shorter follow-up period (median, 2.1 years) in these studies may have underestimated the benefit of interferon therapy. A recently published meta-analysis showed that antiviral treatment was associated with a reduced risk of HCC in patients who reached a SVR compared to non-receptors; the best results were seen in patients treated with ribavirin-based regimens, which confirms the results of other meta-analysis [–]. The achievement of SVR also demonstrated the prevention of the development of esophageal varices []. There have been case reports [] and long-term follow-up studies that have shown the development of HCC in patients with advanced liver fibrosis after the realization of a SVR [, , , , , , ]. In a follow-up study, the two patients who developed HCC were diagnosed 5.8 and 7.3 years after reaching a SVR. These observations highlight the constant risk of HCC and the need for continuous surveillance with imaging and alphafetoprotein tests in patients with chronic hepatitis C and advanced liver fibrosis, even after a SVR. In short, several studies have shown that the achievement of an antiviral therapy SVR reduces, but does not eliminate, the incidence of HCC and decreases liver-related complications and mortality in patients with chronic hepatitis C, and in some studies also in cirrhosis. However, the effect of antiviral therapy is controversial in patients who were aided during treatment and later relapsed after treatment and probably has a limited benefit in non-receptors.8. Preventive effect of the interferon on repetition of the tumor after treatment of HCCTo evaluate the effects of interferon treatment on HCC recurrence after HCC resection, studies were conducted in which patients were randomized to receive interferon treatment or to remain. Patients from the interfering group received alpha for approximately 2 years, but only 2 patients (13%) achieved a VS. HCC recurrence was observed in 33 per cent of the interfering group and in 80 per cent of the control group. The recurrence rate was significantly lower and the significantly higher accumulated survival rate in the interferon group than in the control group [, ]. In another randomized controlled study, 74 patients with cirrhosis and low loads of HCV RNA were assigned to receive interferon for 1 year () or an untreated control group () after the complete ablation of HCC for percutaneous ethanol injection therapy []. SVR was achieved in 29% of patients. Interferon treatment seemed to eliminate the rate of a second or third recurrence of HCC, but not a first recurrence, and improve the survival rate. Several studies, including a meta-analysis with an exception, indicate that the achievement of VSL appears to prevent the recurrence of HCC [–]. However, since virtually all of these studies were conducted in Japan, a final conclusion should expect more reports from other regions of the world.9. Impact of Maintenance Therapy on the Results of Chronic Hepatitis with Advanced Fibrosis A previous randomized controlled trial revealed that the long-term low-dose interferon treatment for patients who did not obtain a SVR with pre-feron therapy improved liver histology [] (Table ). In addition, Nishiguchi and others [,] showed that interferon monotherapy for 12 to 24 weeks reduced the occurrence of HCC and disease progression. Although these studies included a small number of patients, the results encouraged clinicians to undertake major studies to confirm the impact of chronic hepatitis C maintenance therapy with advanced liver fibrosis. (North of study) (North of birth) Patients in both arms received a 6-month course of IFN monotherapy before randomization. (b) N/A = unavailable. (c) 36% and 44% of patients had not responded to IFN monotherapy and IFN/ribavirin combined therapy, respectively. (d) Patients received no response to peginterferon of instructional phase of 6 or 12 months plus ribavirin treatment. (e) A summary is available only. (f) Patients did not receive a response to previous therapy. (g) Eventless survival was better only in patients with portal hypertension. (h) Patients did not receive a response to the previous more ribavirin interferon therapy. (i) Clinical events were less frequently observed in the treated group in patients with esophageal reference varices. (North of study) (North of birth) These patients were randomized to receive no therapy or peginterferon alfa-2a at a dose of 90 g per week for 3.5 years. Although serum aminotransferase levels, serum HCV RNA levels and necro-inflammatory scores significantly decreased with therapy, the primary results rate (death, HCC, liver decompensation, or an increase in Ishak score of 2 or more) was similar in treatment and control groups (34.1% and 33.8%, respectively), confirming a relatively small number of test results, confirming a previous number of treatment and control. In the HALT-C study, viral deletion of 4 log10 during the targeted therapy phase was associated with a significant reduction in clinical outcomes, although there was no significant difference between treatment and control groups []. Unexpectedly, viral deletion of 4 log10 during the maintenance therapy phase did not result in an improvement in clinical outcomes. A decrease in the levels of serum HCV RNA could improve the clinical result, even if it is short and transient; therefore, viral deletion during the entry phase may have obscured the beneficial effect of maintenance therapy. Nishiguchi's study tested interferon naive patients, who may have accentuated the beneficial effects of the interferon []. 16 percent of treated patients achieved a SVR in this study, which is unlikely in studies that inscribe previous non-receptors. The results of two other major randomized trials are currently unpublished. In the COPILOT study, patients with an Ishak fibrosis score of 3 or more were not interferon therapy receptors to receive peginterferon alfa-2b, at a dose of 0.5 g/kg weekly, or cochicin. This maintenance therapy significantly slowed the development of varicose bleeding, but did not affect the overall result [, ]. The study also revealed that maintenance therapy was not superior to control except in the reduction of clinical events in patients with esophageal varices []. Finally, a recent meta-analysis that evaluates the role of non-receptor interferon therapy did not reduce the incidence of HCC (RR: 0.58; 95% CI: 0.33–1.03) []. In short, there is insufficient data to recommend maintenance therapy for patients who did not respond to the previous interferon treatment. In the HALT-C study, 3.5 years of low-dose peginterferon improved histological necroinflammation scores, but did not reduce the rate of progression of the disease. Histology of the liver, especially fibrosis, is closely associated with the prognosis [, , , ]. Therefore, additional follow-up of patients in the HALT-C trial can confirm the inhibitive effect of maintenance therapy in the progression of liver disease. 10. Conclusions The long-term benefit of antiviral therapy, including reduction of liver fibrosis, lower incidence of HCC and long-term life expectancy, appears to be limited primarily to patients capable of achieving a SVR. A recent systematic review showed that health-related quality of life was also improved and that antiviral treatment is reasonably cost-effective in patients with treatment diseases, as well as relapses and non-receptors []. Therefore, doctors should treat with antiviral therapy, with the aim of achieving an early SVR in the natural history of chronic hepatitis C. Direct action antiviral agents (ADA) provide new treatment options for chronic hepatitis C management in the near future. Telaprevir, a NS3 HCV protease inhibitor, in combination with peginterferon and ribavirin, induced SVR at approximately 70% of the genotype 1 of the treatment and 51% of the patients who failed the previous peginterferon plus ribavirin therapy [–]. The increase in the rate of SVR using ASD agents can provide a long-term benefit to a wider range of patients, including peginterferon receptors and ribavirin therapy, and further improve the long-term results of therapy including slowed fibrosis progression, lower incidence of HCC and long-term life expectancy. ReferencesCopyrightCopyright © 2010 Tatehiro Kagawa and Emmet B. Keeffe. This is an open access article distributed under the article, which allows unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided that the original work is duly cited. More related articles Share Related articles

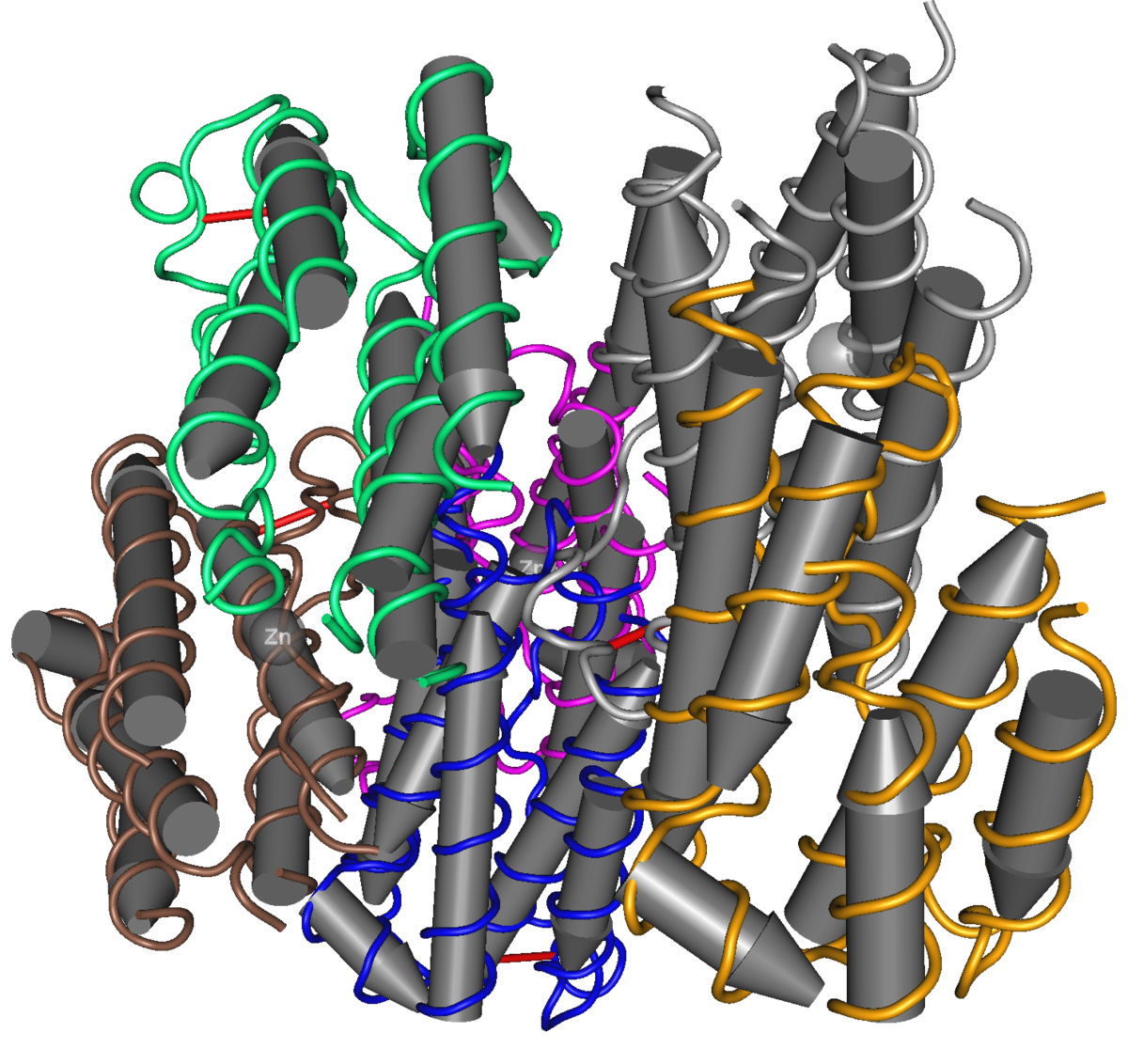

Pegylated interferon

Interferon: Long-Term Side Effects

Interferon: Long-Term Side Effects

Interferons and Long-Term Side Effects | Hepatitis Central

Ribavirin Long-Term Side Effects

Treatment of chronic hepatitis C in treatment-naïve patients

Psychological side effects of immune therapies: symptoms and pathomechanism - ScienceDirect

Interferon: Long-Term Side Effects

Using Pegylated Interferon and Ribavirin to Treat Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C - American Family Physician

Long-term effect of early treatment with interferon beta-1b after a first clinical event suggestive of multiple sclerosis: 5-year active treatment extension of the phase 3 BENEFIT trial - The Lancet Neurology

Interferon - Wikipedia

Triple combination of interferon beta-1b, lopinavir–ritonavir, and ribavirin in the treatment of patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19: an open-label, randomised, phase 2 trial - The Lancet

Differences between PEG-interferon-based regimens and DAAs.... | Download Table

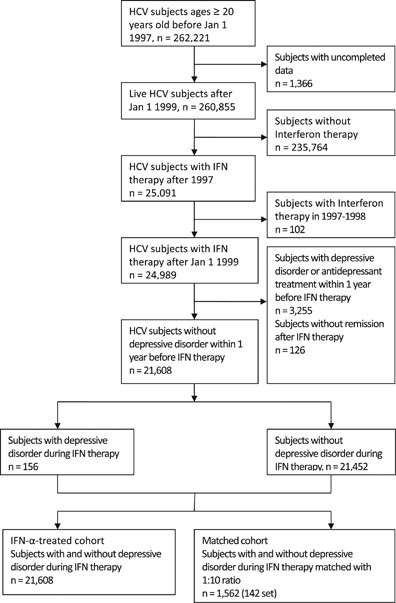

Recurrence of depressive disorders after interferon-induced depression | Translational Psychiatry

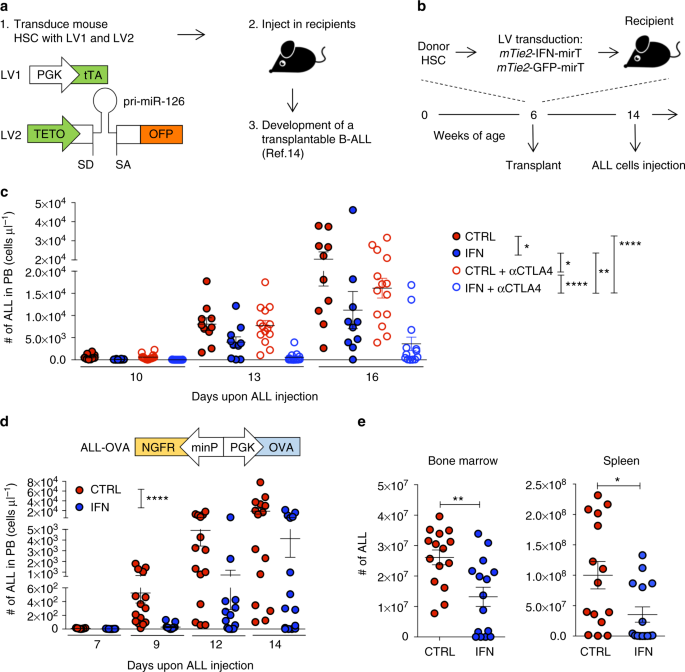

Interferon gene therapy reprograms the leukemia microenvironment inducing protective immunity to multiple tumor antigens | Nature Communications

A clinical pilot study on the safety and efficacy of aerosol inhalation treatment of IFN-κ plus TFF2 in patients with moderate COVID-19 - EClinicalMedicine

The innovative development in interferon beta treatments of relapsing‐remitting multiple sclerosis - Madsen - 2017 - Brain and Behavior - Wiley Online Library

Interferon side effects: Signs, causes, and risks

Psychological side effects of immune therapies: symptoms and pathomechanism - ScienceDirect

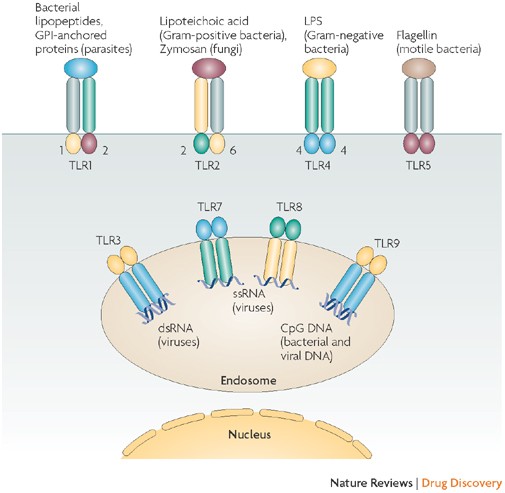

Interferons at age 50: past, current and future impact on biomedicine | Nature Reviews Drug Discovery

Autoantibodies against type I IFNs in patients with life-threatening COVID-19 | Science

Effect on HBs antigen clearance of addition of pegylated interferon alfa-2a to nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy versus nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy alone in patients with HBe antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B and sustained undetectable plasma

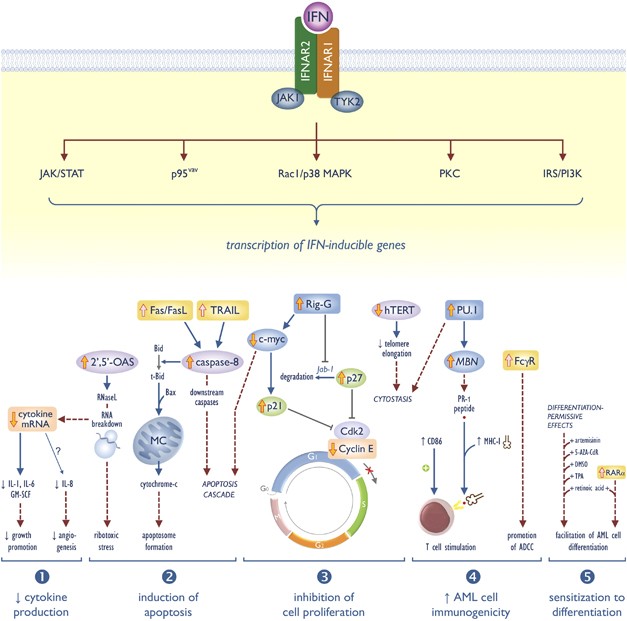

Interferon-α in acute myeloid leukemia: an old drug revisited | Leukemia

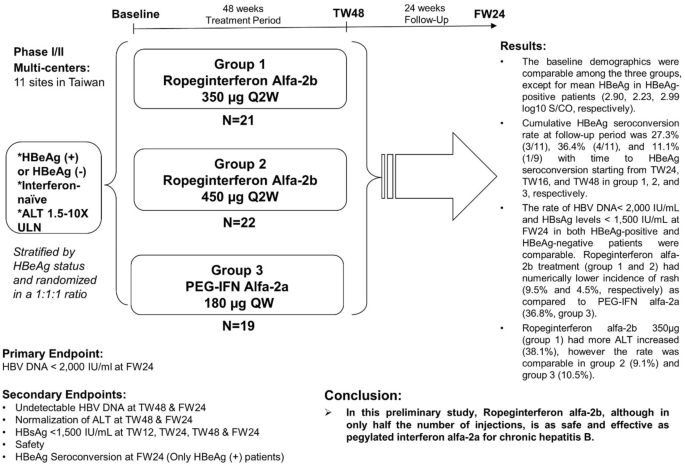

Ropeginterferon alfa-2b every 2 weeks as a novel pegylated interferon for patients with chronic hepatitis B | SpringerLink

Hepatitis B Treatment: What We Know Now and What Remains to Be Researched - Suk‐Fong Lok - 2019 - Hepatology Communications - Wiley Online Library

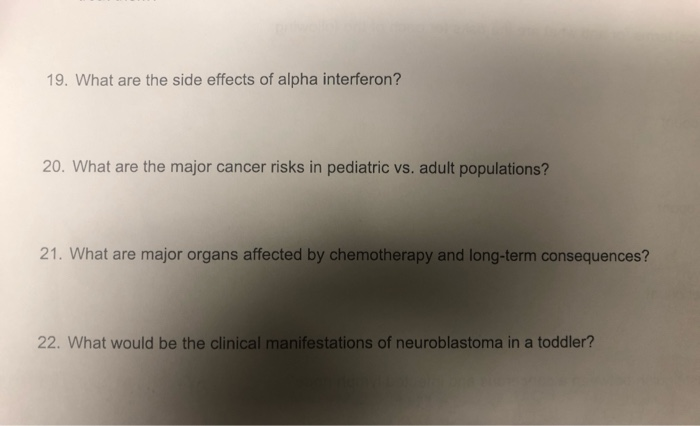

Solved: 19. What Are The Side Effects Of Alpha Interferon?... | Chegg.com

Safety and efficacy of inhaled nebulised interferon beta-1a (SNG001) for treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial - The Lancet Respiratory Medicine

Interferon - Wikipedia

Factors influencing long‐term changes in mental health after interferon‐alpha treatment of chronic hepatitis C - SCHMIDT - 2009 - Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics - Wiley Online Library

Genetic Lesions of Type I Interferon Signalling in Human Antiviral Immunity: Trends in Genetics

Does interferon therapy work in COVID-19?

Interferon beta-1a - Wikipedia

/pegasys-568530305f9b586a9e15ec79.jpg)

Treating Hepatitis With Pegylated Interferon

Type I Interferon Delivery by iPSC-Derived Myeloid Cells Elicits Antitumor Immunity via XCR1+ Dendritic Cells - ScienceDirect

Long-term impact of inhaled corticosteroid use in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): Review of mechanisms that underlie risks - Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology

Interferon side effects: Signs, causes, and risks

Direct Effects of Type I Interferons on Cells of the Immune System | Clinical Cancer Research

PDF) Interferons and multiple sclerosis: Is it plausible that β-IFN treatment could influence the risk of cancer among MS patients?

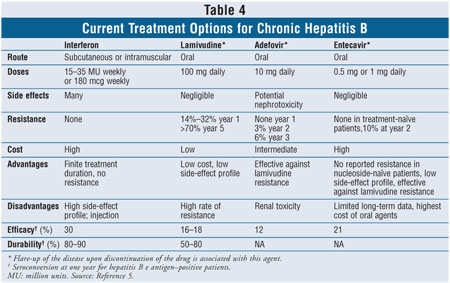

Chronic Hepatitis B Infection

Visualizing the Selectivity and Dynamics of Interferon Signaling In Vivo - ScienceDirect

Posting Komentar untuk "interferon long term side effects"